The Air Force now says it may want a 6th generation fighter that costs around $100M instead of $300M, but is that even possible?

The Air Force’s long-touted 6th generation Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) crewed ‘fighter’ program is under deep review, with massive revisions to what the service wants out of it being a real possibility at this point. After originally stating this very advanced aircraft that would sit as the centerpiece of the NGAD family of systems would cost roughly three times that of a new F-35 (upwards of $300M plus each), Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall is now eying pursuing a far less expensive aircraft, one that will cost around what a fresh F-35 or F-15EX does, which is very roughly around $90M-$100M apiece.

At the Air & Space Forces Association’s 2024 Air, Space, Cyber conference outside of Washington, D.C. last week, Secretary Kendall told reporters, including TWZ’s Howard Altman, that the reevaluation of what the USAF wants out of the NGAD crewed jet is underway and by his own words, the resulting changes could be dramatic:

“I’ll just give you this off the top of my head here, that the F-35 kind of represents, to me, the upper bounds of what we’d like to pay for an individual [NGAD] aircraft for that mission. … The F 15EX and F-35 are roughly in the same cost category. I’d like to go lower though. There are – once you start integrating CCAs and transferring some mission equipment and capabilities [and] functions to the CCAs, then you can talk about a different concept, potentially, for the crewed fighter that’s controlling them. So there’s a real range in there. We need a unit cost that’s affordable in significant numbers, though. So that’s part of the equation. And, I mean, NGAD [the original combat jet concept] itself is still a possibility. It’s one of the things we’re looking at. But the numbers there are, you know, as I’ve said in public before, they’re multiples of an F-35 right? So we’d like to get down from that. But if that turns out to be the most cost effective operational answer, that’s what we’re gonna do and go fight for the money to have it. You end up with small numbers. I mean, the more the airplane costs, the fewer of them you’re gonna have. Numbers do matter. So it’s a trade off.”

So what could a 6th generation fighter that costs one-third of the original NGAD requirements actually look like? Is it even possible?

Let’s get into it.

Decentralizing/distributing to the extreme

As we have discussed for years, the crewed NGAD component was being designed from the ground up as a central part of an ecosystem of next-generation tactical air combat technologies. These include above all else Collaborative Combat Aircraft ‘loyal wingmen’ drones, but also new weapons, communications architectures, sensors, engines, and more. They could also include other types of undisclosed drones, but more advanced, independent-operating, deep-penetrating types of the tactical variety don’t seem to be even on the table at this time. You can read more about that in our recent reporting here.

One advantage of such a ‘family of systems’ is that critical features that had to be on every single fighter of the same type in the past can be distributed across multiple platforms. For instance, if the goal is just about getting a human in the loop within line-of-sight to control CCAs and manage the tactical ballet, the fighter could have no radar or any other types of sensors of its own. Instead, radars, infrared search and track systems (IRST), and electronic support measures, as well as electronic warfare capabilities, could be dispersed to modular CCAs and potentially other platforms in their vicinity. Some of these functions could even provided by space-based platforms/constellations and data-linked to the aircraft in real time.

While this may be possible, it’s very risky and it takes the distributed sensor concept to the extreme. It also severely limits the aircraft’s applications when CCAs are not in use. It still would be prudent to give the fighter some independent sensing capabilities, perhaps a single radar array for use cooperatively with other platforms and as a fallback for certain tactical contingencies — more on that in a minute.

A far more elaborate installation of cutting-edge multi-mode arrays distributed around or even made part of the airframe itself may not be within the cost limitations of a revised NGAD fighter program. You can read all about this capability here. Still, the NGAD fighter relying more heavily on CCAs for these functions has some upside. These drones will fly closer to targeted threat areas anyway and they will be data-linked together, allowing for cooperative sensing tactics and a higher degree of triangulation of targets, which in many cases would provide superior fidelity and more resilient sensor data. This is exactly the distributed payload concept we described in great detail back in 2016 and the USAF has become increasingly focused on it as of late. Aircraft like the XQ-67 Off-Board Sensing Station (OBSS) appear to be a trial platform for just this kind of sensor-carrying tactical drone, for instance, but CCAs will be capable of being configured for these roles, as well.

Still, by relying on distributed sensor and electronic warfare payloads for CCAs more heavily, the NGAD fighter will be less capable on its own, especially in a very high-end fight. This would mean that the drone and crewed fighter will be tied even closer together operationally, with the fighter depending on them and the networking that connects to them even more heavily for tactical success. There are also logistical and attrition concerns with such a bet, but a balance more heavily weighted toward CCA when it comes to sensor and electronic warfare system deployment is more likely than going to the extreme end of the distributed concept and stripping the manned aircraft of most or even all of its sensors.

While removing advanced sensors and electronic warfare gear from an aircraft, or replacing these systems with simpler options, would definitely save on cost and it could help reduce the size of airframe itself, where the cost really comes into play is payload, range, and speed.

Payload reduction

NGAD was always largely thought to be a heavy interceptor-like aircraft, featuring a comparatively very large combat radius that is optimized for fighting in the Pacific where tankers will be pushed back beyond the range of most fighter aircraft to their target areas, at least early in a conflict. It would also have to carry a large payload of diverse weaponry internally so that it can maintain its low-observable (stealth) abilities that would be critical to its survival while also delivering a heavy punch deep inside contested airspace. Just for the air dominance role, not deep strike, a large number of air-to-air and suppression/destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD) weapons would be needed for the aircraft to fight its way in and out of an area where external support would be extremely limited. Two factors could drastically change this calculus.

The first is a much heavier reliance on CCAs for standard weapons carriage and on other platforms for larger, outsized weapons delivery. Putting the magazine depth focus more on drones instead of the central controlling platform could drastically reduce the size of aircraft needed to perform the mission. It could be argued that it would also provide a greater degree of survivability in some situations as the crewed asset would not have to (or even have a reason to in some cases) get within launch distance of many threats. Instead, the CCAs almost exclusively would, with the fighter element hanging even further back at a safer distance than originally planned. Such tactics could also become more pressing as enemy air defense capabilities continue to evolve, specifically when it comes to fusing information from various sensors to spot even very stealthy aircraft at a distance.

A massive reduction in payload requirement and likely the inclusion of more CCAs on a typical mission would also allow for more tactical flexibility in some instances. Larger weapons, such as very long-range air-to-air missiles, could be carried by assets like the B-21 Raider deeper into contested environments, while F-15EXs and B-52s could do the same along the outer edge of higher-threat areas, at least in some situations. These aircraft could launch these weapons on demand of the crewed NGAD fighter operating far forward. It could even be argued that funds set aside for a very costly NGAD fighter could be partially invested in buying additional B-21s and even F-15EXs to support NGAD-related air dominance missions.

Reducing the payload requirements of the NGAD fighter would reduce the complexity and size of the fighter platform. This could save a lot of money, as everything from the propulsion requirements to the physical size of the airframe would be decreased.

This is not to say such a configuration would be unarmed. Still, reducing its weapons bay size to carry say a quartet of AIM-120s or AIM-260s, along with a pair of AIM-9X Sidewinders or four Small Diameter Bomb (SDB) sized air-to-ground weapons, could be enough for contingencies and for mundane operations in less contested airspace, such as in the Middle East, where CCAs may not even be a factor for normal missions.

Less gas

An even bigger factor is fuel. It is valid to assume that the original NGAD concept placed fuel carriage as a premium design driver. This aircraft had to fly far from tanker support, into the enemy’s anti-access bubble and back in order to be relevant. Now the USAF is increasingly aggressive about fielding a stealthy tanker that can operate at least at the very edge of contested airspace.

America’s tactical airpower was not built for fighting over long distances without tanker support being in relatively close proximity. Its fighters have combat radii roughly between 350 and 850 miles or so. This puts the tankers at risk as an enemy’s anti-access bubble can now extend many hundreds and even thousands of miles from its territory. NGAD and CCAs, which will have significantly larger combat radii than current fighter aircraft, were viewed as a way to correct for this huge capability gap, but if the USAF is now moving to build a stealth tanker, the need for a much longer-ranged 6th generation crewed tactical jet could be offset to some degree.

TWZ made the case for a stealth tanker years ago based on all these issues and more. At the time many blew it off as fantasy. This is no longer the case as the factors that dictate the need for such a capability have only grown more pressing in recent years as the U.S. military faces a potential massive fight in the Pacific with China and as air defenses become ever-more sophisticated and longer-ranged. The USAF is now accelerating its next-generation tanker initiatives with an increasing focus on fielding low-observable tankers, which it just said will be directly tied to its final NGAD plans.

So, if the USAF is willing to assume a lot more risk while also committing to fast-tracking a stealthy tanker, it could possibly justify a NGAD fighter with a significantly smaller combat radius and shrink the cost and complexity of the airframe even further.

Slower and lower

Then there are the kinematic performance concessions that could be made with a revised NGAD design. In a previous thought piece, we explored the possible performance targets of the crewed NGAD component. You can check that feature out here. Regardless, the ability to fly higher and faster for longer periods of time, even while deeply sacrificing maneuverability, are likely design drivers. Sustained supercruise (flying over Mach 1 without the use of afterburner) and higher ceilings while also not guzzling precious fuel come at a heavy cost. The F-22, for instance, is well known for its supercruise capability, but it still zaps the jet’s endurance and is used for high-risk tactical portions of a mission, not for regularly transiting longer distances faster. Flying at higher altitudes, like the F-22 which can operate normally at altitudes in excess of 60,000 feet, is also a major plus. Just the ability to give sensors and datalinks a much longer line-of-sight is a big plus, as is the additional range imparted onto weapons fired at those altitudes.

By relaxing high or even breakthrough performance requirements, with all the material science and development costs that goes with it, an airframe could drop in complexity and cost fairly dramatically.

Maybe above all else, reducing the goals of NGAD’s next-generation engine initiative, the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) program, alongside reductions in performance targets could also save a lot of money, both in development costs and eventual production expenditures. Using a derivative of an existing powerplant, and a single one possibly instead of two, would be even one step further in cost reduction, but with all this would come degraded performance and less advancement in engine technologies, which is a real concern long-term.

Borrow everything you can

Borrowing existing subsystems more deeply could also save a lot of money and development time. For instance, leveraging and adapting the F-35’s Block IV digital backbone and software, as well as even some sensors and communications systems, and scaling in or out other features, could result in a large acceleration of the program and reduction in cost. It would also benefit from large economies of scale baked into the F-35 program, as well as its existing expansive sustainment infrastructure that will exist for decades.

There is a real push for the USAF to retain rights to the NGAD aircraft’s intellectual property and not be locked into one vendor. Deeply adapting a partially off-the-shelf architecture may not be able to achieve this goal, but it could be seen as a worthy trade if deep cost-cutting up-front is seen as more important.

When paired with major performance reductions, mechanical subsystems could also be more easily carried over from other platforms to the ‘cheap’ NGAD fighter concept. There is a long track record of this in the past, especially with smaller-run aircraft, like the F-117, and experimental aircraft. But it is also worth noting that it is well known that the B-21 program strategically leveraged a mix of mature and semi-mature subsystems to speed development and keep costs on track. The USAF would be clearly keen on this practice considering the B-21’s success thus far.

Leaving breakthrough capabilities behind

Having a new aircraft with every bell and whistle possible is becoming less realistic as costs of new weapons systems and the dollars needed to sustain them skyrockets. This means that some major new features that were planned for the $300M NGAD fighter may not make the cut. Even having the capacity to install them in the future could also be left on the cutting room floor in an effort to make the aircraft affordable.

One example of this kind of sacrifice could be laser weaponry, which was envisioned as a core feature of NGAD, but putting these systems on aircraft has since hit massive snags. The weight, volume, complexity, power generation and thermal management needed in order to field even a defensive laser system would be significant. As the airframe, payload and performance shrinks, this becomes a clearer mismatch and the technological hurdles that remain could be seen as major stumbling block for the program. Even the AC-130 has lost its laser weapon before it even arrived for a number of factors, but integrating a system like that onto a cargo aircraft is far less complex than an advanced stealth fighter.

There are a number of other similar concepts that may have to remain aspirational or find their way onto other platforms so that an NGAD fighter can actually get built.

Reductions in all these areas would absolutely result in a significantly cheaper aircraft, but it would also mean trading a massive amount of capability in the process, while also gambling even more heavily on the CCA concept, which still remains… a concept. Certainly, some will ask why not just use the F-35? This likely comes down to the most important factor on this rundown: survivability.

Advanced shell, less advanced core

What this airframe would likely retain in common with its three times more expensive progenitor option is a very high degree of broadband low-observability (stealth), allowing it to operate close to the core of highly advanced integrated air defense networks.

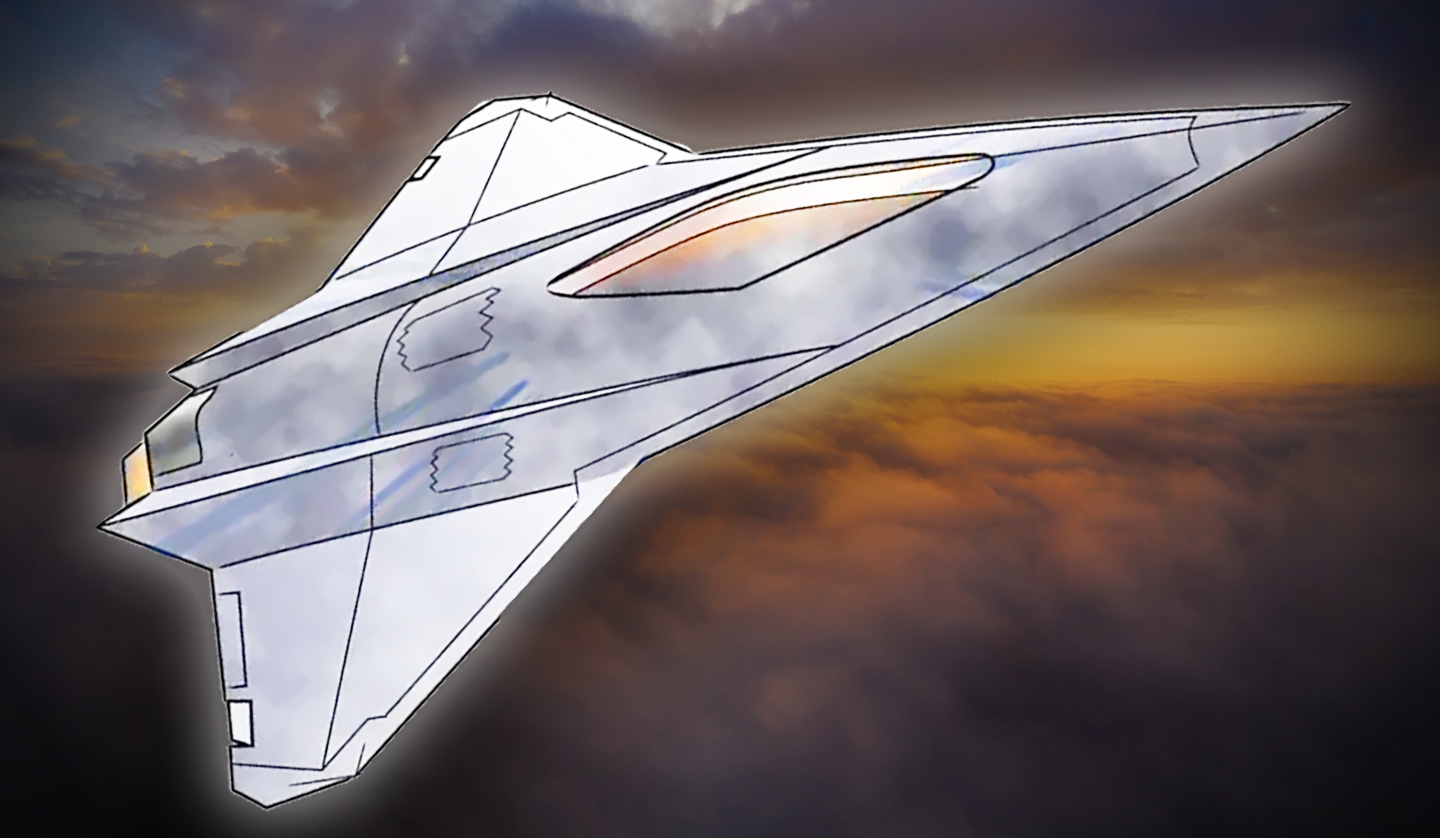

A tailless new-generation stealth airframe could really be a primary feature.

Putting a priority on efficient propulsion and minimizing weapons payload could still provide a notably larger combat radius than the F-35, although the F-35A and C are towards the top end of the existing fighter combat radius scale as it is. This aircraft’s central goal could be refocused on keeping the human pilot alive and present far forward at the technical edge to employ CCAs and to leverage the rest of the NGAD ecosystem to achieve desired outcomes. Its ability as a long-range heavy fighter let alone strike aircraft for truly independent operations would be far more limited. It could rely more on future advances in ancillary and distributed technologies to remain relevant than purely its installed ‘bleeding edge’ capabilities.

So what we could be talking about is a smaller, lighter, less armed, less independent, and shorter-ranged concept that still puts a premium on low-observable technologies. Interestingly, in some ways, such a switch would mirror what happened with the Next Generation Bomber (NGB). It was an absolute top-of-the-line design initiative that was later soft-cancelled and out of its ashes came the Long-Range Strike-Bomber (LRS-B) program. This was a far less ambitious initiative that focused heavily on cost and timeline controls, repurposing mature and semi-mature components and technologies, and rationalizing what is essential and what is not — including payload — and then wrapping it in a very stealthy next-generation broadband low-observable package. It too would also rely on a ‘family of systems’ made up of unique technologies and platforms to successfully complete its future missions.

Does this sound familiar in relation to the changing messaging from the USAF brass on NGAD? It should.

What’s also interesting is the USAF abstractly floated a 6th generation light-to-medium fighter concept recently, although they just said it was a thought exercise, not indicative of a real plan. But even introducing such an idea, including concept art to support it, is an odd move when the service is focusing on getting all its top priorities met, including investments in F-35, F-15EX, NGAD, CCA, and especially incredibly costly nuclear modernization. It seems like there could be a bit more to that ‘thought exercise’ than what we were told, which is what we thought at the time. That doesn’t mean a cheap NGAD fighter would look like what was shown, that really wouldn’t make sense, but it certainly fits the general direction that is now formally on the table.

Even with this big cocktail of measures focused on drastically reducing the unit price of a future NGAD fighter aircraft, could it really be dropped to around $100M? It’s tough to say. If most of what is described above was done to the maximum logical extent, it may be possible once the type hits full-rate production, if the latest in manufacturing techniques are brought to bear, as well. Still, that seems like a stretch, especially without increasing the buy far beyond the 200 airframes Kendall has floated before. If that number is drastically expanded, it would have a better chance of meeting that price target.

Above all else, what we do know now is the flying service remains behind the curve and still uncertain of how it will maintain air supremacy in a rapidly changing security environment in which peer competition hasn’t been as tangible as it is today for decades. Can the USAF really stay ahead of China by going the much cheaper route for its crewed NGAD component? Or is the better course to just focus on and broaden the uncrewed technology side of the portfolio and divert funds away from a crewed NGAD aircraft altogether?

We will be addressing these larger issues in another future piece, but as it sits now, it sure seems like the NGAD fighter program could be about to change, and fairly dramatically so.