The supercarrier’s silhouette hasn’t changed much over the past 50 years, but one utilitarian staple of the flight deck has gone the way of the dodo bird.

t was a common poster on the wall of boys growing up, and it probably still is today—the imposing heading-on view of a fully loaded American supercarrier bristling with fighters and support aircraft. On the bow of these most complex of fighting ships, two prong-like structures stuck out over the water, ramped downward as if to give the aircraft riding along the ship’s catapult tracks a few extra feet of help before leaping into the air. The strange protrusions gave these ship’s an ever more menacing appearance, but over the last few decades they have disappeared from American supercarriers. So what were they and where did they go?

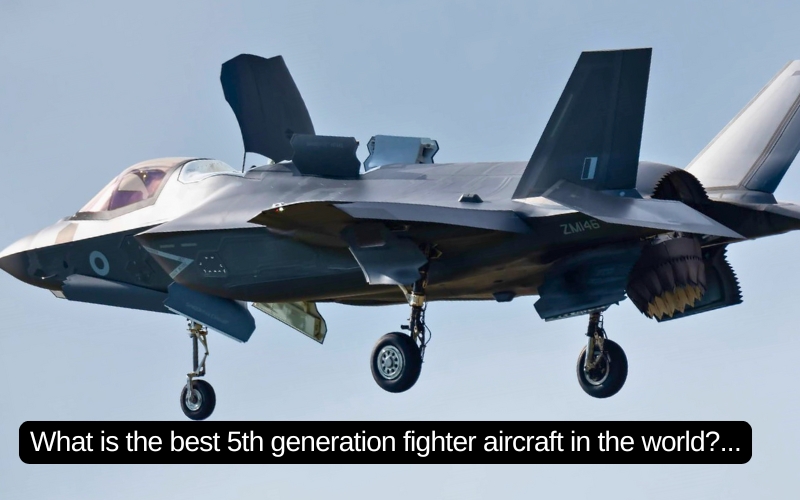

The USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) AKA “Big John” seen underway from an impressive angle (Huntington Ingalls image):

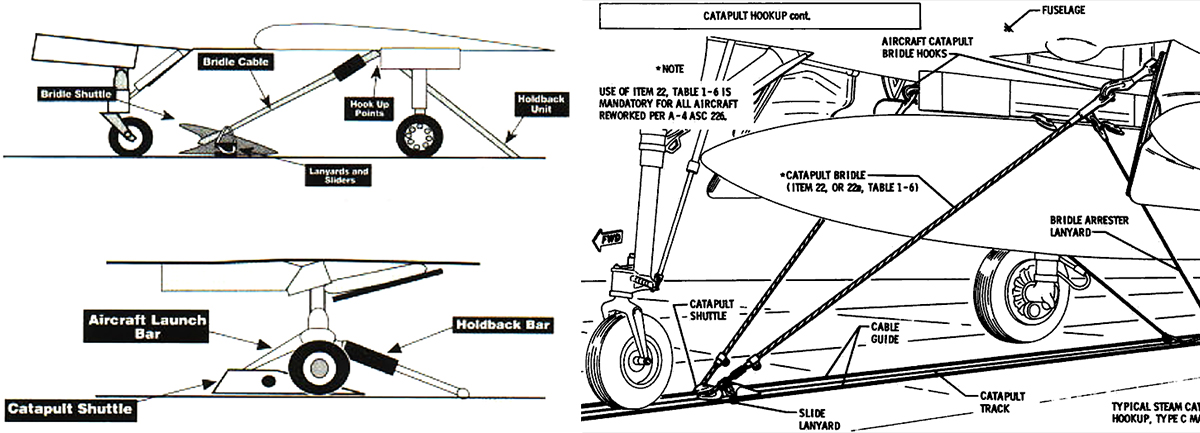

Enter the “bridle catch,” also known as a “bridle arrestment sponson,” a utilitarian structure used to catch the slinging bridles that attached carrier-borne naval aircraft of yesteryear to their host ship’s catapults. A bridle was a heavy-duty cable-like lanyard that attached to rearward facing hooks on either side of the aircraft, and would then run down toward the deck in a “v” to be attached to a single-point notch in the catapult’s shuttle. A similar single line device was also used on some aircraft like the S-2 Tracker, it was called a pendant.

A VF-111 Sundowner F-4B seen being strapped in via a bridle before launch aboard the USS Coral Sea during the Vietnam War:

Once the green shirts hooked the aircraft up to the catapult and it fired (read all about this process here), the bridle or pendant that links the shuttle to the aircraft would pull it down the catapult track at increasing speed. At the end of the deck the aircraft would depart into the air. The bridle or pendant would then be flung out into the sea, or if the carrier was so equipped, it would whip down onto the sloped bridle catcher so that it could be recovered and used again and again. In essence the bridle catcher was a feature of economy more than anything else. The reason for angling the bridle carrier extension downward was so the bridle would not bounce up and strike the aircraft as it left the deck.

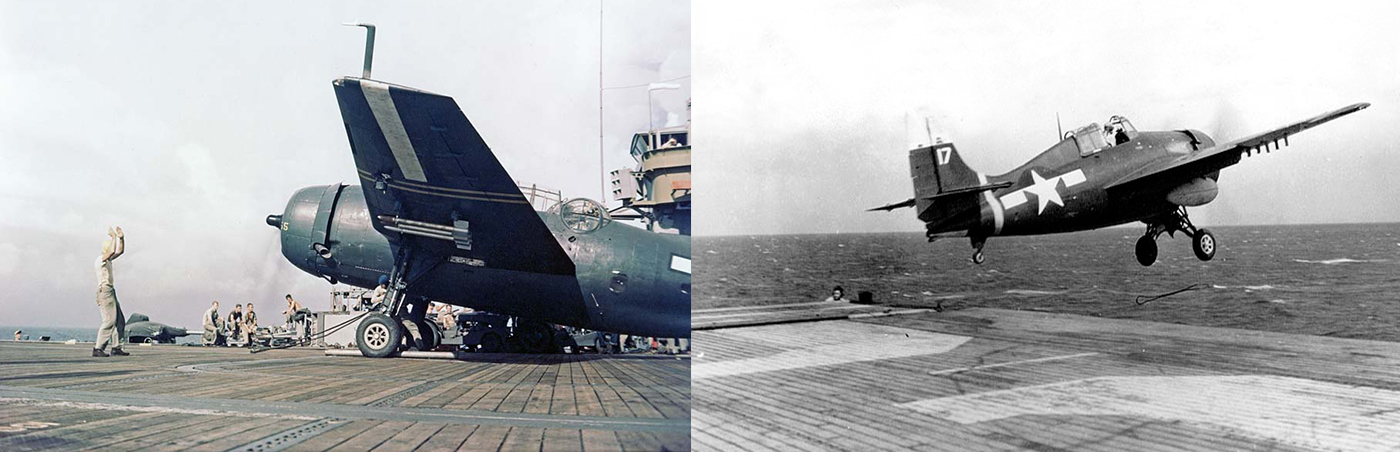

A TBM Avenger (left) seen with a bridle attached while sailing aboard the USS Cape Gloucester in 1945. A FM-2 Wildcat (right) seen launching off the deck of the USS Makin Island, bridle being hurling into the ocean, in 1945:

The bridle and pendant system got Navy carriers into the catapult business, but the system was more complex and time consuming than it had to be. There were always concerns over broken bridles and connection points, and the wellbeing of carrier deck crews that had to strap the big aircraft in before each launch was of an even greater concern. It wasn’t until the early 1960s and the introduction of the E-2 Hawkeye (W2F-1 at the time) that the bridle was replaced by the integral catapult launch-bar attached to the aircraft’s nose gear.

Diagrams detailing and comparing the two systems:

The first launch by an E-2 using the system occurred on the 19th of December, 1962. Tests were largely successful and substantial gains in safety and efficiency were realized by the new system. Going forward every new US Navy aircraft designed for carrier operations would be equipped with a similar nose gear mounted launch bar.

An E-2A being launched via its integral launch bar from the USS Oriskany in the early 1960s (San Diego Air & Space Museum photo):

Over time, as older aircraft that used bridles and pendants were retired, bridle catchers would begin to disappear from America’s aircraft carriers. The last carrier built with bridle catchers was the third Nimitz class nuclear supercarrier, the USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70), which began construction in 1975 and was officially commissioned into the fleet in 1982.

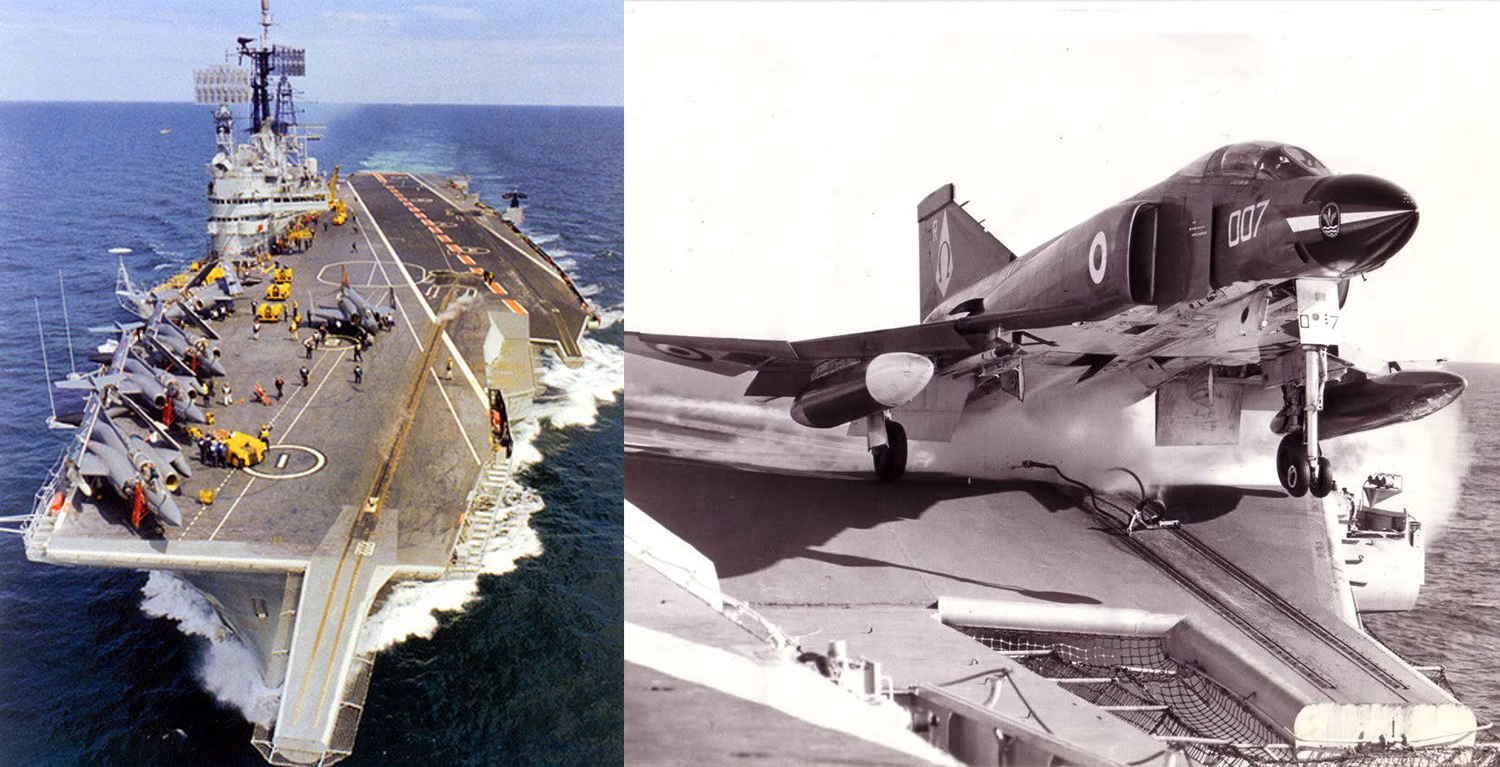

The Royal Navy’s Audacious class carriers featured bridle catchers on both the bow and the waist catapults, as seem on the HMS Ark Royal (R09) below:

Towards the end of the millennium, American supercarriers that had bridle catchers began having them removed during deep maintenance and overhaul periods. The last active US carrier to have them was the USS Enterprise (CVN-65) which pulled into Naval Station Norfolk for inactivation with her bridle catchers still intact on November 4th, 2012.

Just last July, the last NATO fixed-wing carrier aircraft to use a bridle, the French Super Étendards Mordernise (SEM), was retired once and for all. The carrier these aircraft operated from, the Charles De Gaulle (R91), was never built with bridle catchers. For many years SEMs slung bridles into the sea with reckless abandon.

A SEM launching off the deck of the Charles De Gaulle:

Here the catapulting of the fighter aircraft Super Etendard.

Toulon, France 13/01/2015

Credit : Lilian Auffret / Sipa/AUFFRET_1123.029/Credit:LILIAN AUFFRET/SIPA/1501171150 (Sipa via AP Images)

Today, really the only aircraft that may see the bridle once again are Brazil’s handful of upgraded AF-1 Skyhawks. Their antique carrier, the surplus French Clemenceau class carrier Foch, now named São Paulo, is supposedly finally getting the upgrades it needs to be operational again. If this indeed comes to pass, its bridle catcher will see use once again—as the last of its kind and a monument to naval aviation’s heritage.

An AF-1 being hooked up to one of the Sao Paulo’s catapults. The carrier has not supported aircraft for nearly a decade but the Brazilian Navy still hopes to return it to service (Photo credit Rob Shleiffert/Wikicommons):