On the remote island of Yap, nestled in the vast Pacific Ocean, is a fascinating monetary system that defies traditional concepts of currency. Enter the realm of the Rai stones, massive limestone discs that were used as a form of money for centuries. These colossal boulders, some weighing several metric tons, hold immense value and serve as a testament to the Yapese people’s intricate cultural and economic practices.

Island of Yap

Situated on the island of Yap, part of Micronesia, are the Rai stones. Their history can be traced back some 500 to 600 years, according to local stories. Supposedly, one of their ancestors led a group of men to the island of Palau, where they discovered a nearly endless source of limestone, something that they didn’t have back in their community.

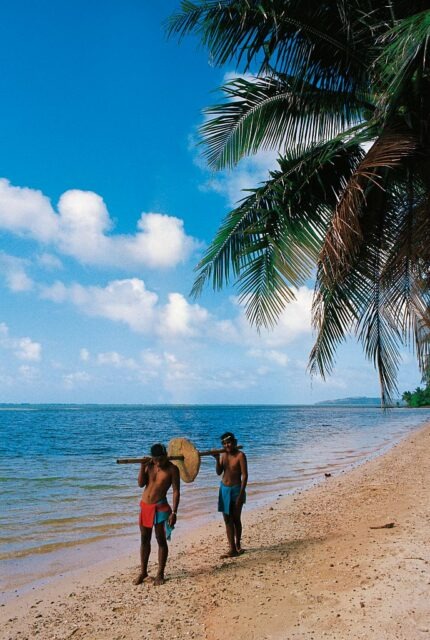

Palau locals allowed the trade of the stone for other goods provided by the Yapese. They carried large slabs on their boats back to their home and then carved these early stones in the shape of different animals – fish, turtles, or lizards. Eventually, the islanders adapted a much more practical circular style.

Monetary origins

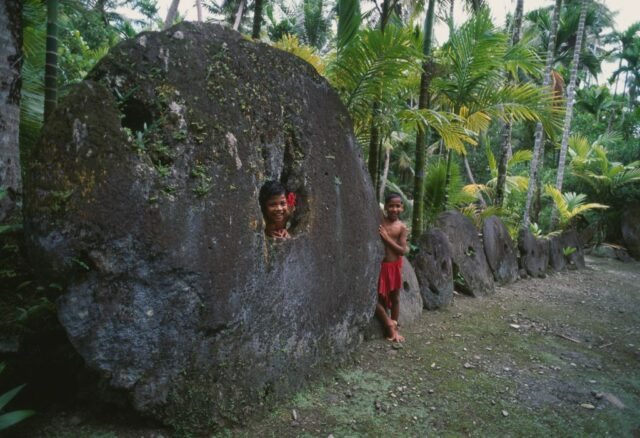

The design was meant to look like a full moon, with a hole in the middle for easier movement around the island. Despite their symbolism now, it’s unknown if the Rai stones always had financial value. Over time, however, this is how they became used.

Once back on Yap, the stones were given to the different high chiefs to manage distribution. They would keep the largest of the stones for themselves and their families, along with a number of the smaller ones.

Big purchases only

The remainder would then be available for the other villagers to purchase by using their older currency system of pearl shell money. As each stone earned a history of its own, it became more valuable in the community and would be worth more when it was given to another person.

Typically, they were so valuable that they were really only used for large or important purchases. North Carolina State University anthropologist Scott Fitzpatrick said, for example, that “If somebody was in real dire straits, and something happened to their crop of food or they were running low on provisions and they had some stone money, they might trade.”

Immovable currency

Other examples were paying a dowry or making amends with another family on the island for wronging them in some manner. Yet, in this instance, because of the vast size of many of the stones, they didn’t physically change hands like coins would.

Instead of physically moving the stones during transactions, the Yapese people simply transferred ownership rights and acknowledged the new keeper through communal consensus. Fitzpatrick recounted one of the island’s stories about honoring the stone currency even when one sunk to the bottom of the ocean.

Changing uses

A work crew was carrying one of the stones back to the island on a boat, and it fell off and sunk. Instead of the owner losing their ‘money,’ the community agreed that it retained its value and the ownership could – and did – pass hands where it lay.

Rai stones are no longer used as a form of money, but they were still used as valid currency well into the 20th century. This partially explains why there are still so many around the island – approximately 6,000 of the large stones. Now, they are really only used in a ceremonial way by the Yapese.

Withstanding the test of time

Not only did the Rai stones withstand colonization on the island, they even stood up to the occupation of the island by Japanese forces during the Second World War. The invading Army did use some of them for construction projects, and as anchors for their ships, but most of them remained intact.

Although new stones are rarely made, some are still created to ensure the skill passes through different generations. These modern versions, however, aren’t valued the same way as the ancient ones. Still, the Rai stones make up an important historical and cultural part of Yapese life and are certainly a site to see.