When Mark Lehner was a teenager in the late 1960s, his parents introduced him to the writings of the famed clairvoyant Edgar Cayce. During one of his trances, Cayce, who died in 1945, saw that refugees from the lost city of Atlantis buried their secrets in a hall of records under the Sphinx and that the hall would be discovered before the end of the 20th century.

In 1971, Lehner, a bored sophomore at the University of North Dakota, wasn’t planning to search for lost civilizations, but he was “looking for something, a meaningful involvement.” He dropped out of school, began hitchhiking and ended up in Virginia Beach, where he sought out Cayce’s son, Hugh Lynn, the head of a holistic medicine and paranormal research foundation his father had started. When the foundation sponsored a group tour of the Giza plateau—the site of the Sphinx and the pyramids on the western outskirts of Cairo—Lehner tagged along. “It was hot and dusty and not very majestic,” he remembers.

Still, he returned, finishing his undergraduate education at the American University of Cairo with support from Cayce’s foundation. Even as he grew skeptical about a lost hall of records, the site’s strange history exerted its pull. “There were thousands of tombs of real people, statues of real people with real names, and none of them figured in the Cayce stories,” he says.

Lehner married an Egyptian woman and spent the ensuing years plying his drafting skills to win work mapping archaeological sites all over Egypt. In 1977, he joined Stanford Research Institute scientists using state-of-the-art remote-sensing equipment to analyze the bedrock under the Sphinx. They found only the cracks and fissures expected of ordinary limestone formations. Working closely with a young Egyptian archaeologist named Zahi Hawass, Lehner also explored and mapped a passage in the Sphinx’s rump, concluding that treasure hunters likely had dug it after the statue was built.

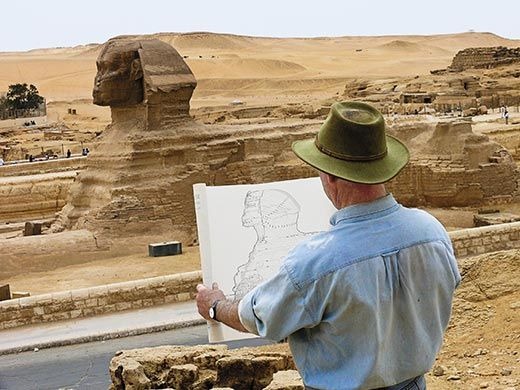

No human endeavor has been more associated with mystery than the huge, ancient lion that has a human head and is seemingly resting on the rocky plateau a stroll from the great pyramids. Fortunately for Lehner, it wasn’t just a metaphor that the Sphinx is a riddle. Little was known for certain about who erected it or when, what it represented and precisely how it related to the pharaonic monuments nearby. So Lehner settled in, working for five years out of a makeshift office between the Sphinx’s colossal paws, subsisting on Nescafé and cheese sandwiches while he examined every square inch of the structure. He remembers “climbing all over the Sphinx like the Lilliputians on Gulliver, and mapping it stone by stone.” The result was a uniquely detailed picture of the statue’s worn, patched surface, which had been subjected to at least five major restoration efforts since 1,400 B.C. The research earned him a doctorate in Egyptology at Yale.

Recognized today as one of the world’s leading Egyptologists and Sphinx authorities, Lehner has conducted field research at Giza during most of the 37 years since his first visit. (Hawass, his friend and frequent collaborator, is the secretary general of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities and controls access to the Sphinx, the pyramids and other government-owned sites and artifacts.) Applying his archaeological sleuthing to the surrounding two-square-mile Giza plateau with its pyramids, temples, quarries and thousands of tombs, Lehner helped confirm what others had speculated—that some parts of the Giza complex, the Sphinx included, make up a vast sacred machine designed to harness the power of the sun to sustain the earthly and divine order. And while he long ago gave up on the fabled library of Atlantis, it’s curious, in light of his early wanderings, that he finally did discover a Lost City.

The Sphinx was not assembled piece by piece but was carved from a single mass of limestone exposed when workers dug a horseshoe-shaped quarry in the Giza plateau. Approximately 66 feet tall and 240 feet long, it is one of the largest and oldest monolithic statues in the world. None of the photos or sketches I’d seen prepared me for the scale. It was a humbling sensation to stand between the creature’s paws, each twice my height and longer than a city bus. I gained sudden empathy for what a mouse must feel like when cornered by a cat.

Nobody knows its original name. Sphinx is the human-headed lion in ancient Greek mythology; the term likely came into use some 2,000 years after the statue was built. There are hundreds of tombs at Giza with hieroglyphic inscriptions dating back some 4,500 years, but not one mentions the statue. “The Egyptians didn’t write history,” says James Allen, an Egyptologist at Brown University, “so we have no solid evidence for what its builders thought the Sphinx was….Certainly something divine, presumably the image of a king, but beyond that is anyone’s guess.” Likewise, the statue’s symbolism is unclear, though inscriptions from the era refer to Ruti, a double lion god that sat at the entrance to the underworld and guarded the horizon where the sun rose and set.

The face, though better preserved than most of the statue, has been battered by centuries of weathering and vandalism. In 1402, an Arab historian reported that a Sufi zealot had disfigured it “to remedy some religious errors.” Yet there are clues to what the face looked like in its prime. Archaeological excavations in the early 19th century found pieces of its carved stone beard and a royal cobra emblem from its headdress. Residues of red pigment are still visible on the face, leading researchers to conclude that at some point, the Sphinx’s entire visage was painted red. Traces of blue and yellow paint elsewhere suggest to Lehner that the Sphinx was once decked out in gaudy comic book colors.

For thousands of years, sand buried the colossus up to its shoulders, creating a vast disembodied head atop the eastern edge of the Sahara. Then, in 1817, a Genoese adventurer, Capt. Giovanni Battista Caviglia, led 160 men in the first modern attempt to dig out the Sphinx. They could not hold back the sand, which poured into their excavation pits nearly as fast as they could dig it out. The Egyptian archaeologist Selim Hassan finally freed the statue from the sand in the late 1930s. “The Sphinx has thus emerged into the landscape out of shadows of what seemed to be an impenetrable oblivion,” the New York Times declared.

The question of who built the Sphinx has long vexed Egyptologists and archaeologists. Lehner, Hawass and others agree it was Pharaoh Khafre, who ruled Egypt during the Old Kingdom, which began around 2,600 B.C. and lasted some 500 years before giving way to civil war and famine. It’s known from hieroglyphic texts that Khafre’s father, Khufu, built the 481-foot-tall Great Pyramid, a quarter mile from where the Sphinx would later be built. Khafre, following a tough act, constructed his own pyramid, ten feet shorter than his father’s, also a quarter of a mile behind the Sphinx. Some of the evidence linking Khafre with the Sphinx comes from Lehner’s research, but the idea dates back to 1853.

That’s when a French archaeologist named Auguste Mariette unearthed a life-size statue of Khafre, carved with startling realism from black volcanic rock, amid the ruins of a building he discovered adjacent to the Sphinx that would later be called the Valley Temple. What’s more, Mariette found the remnants of a stone causeway—a paved, processional road—connecting the Valley Temple to a mortuary temple next to Khafre’s pyramid. Then, in 1925, French archaeologist and engineer Emile Baraize probed the sand directly in front of the Sphinx and discovered yet another Old Kingdom building—now called the Sphinx Temple—strikingly similar in its ground plan to the ruins Mariette had already found.

Despite these clues that a single master building plan tied the Sphinx to Khafre’s pyramid and his temples, some experts continued to speculate that Khufu or other pharaohs had built the statue. Then, in 1980, Lehner recruited a young German geologist, Tom Aigner, who suggested a novel way of showing that the Sphinx was an integral part of Khafre’s larger building complex. Limestone is the result of mud, coral and the shells of plankton-like creatures compressed together over tens of millions of years. Looking at samples from the Sphinx Temple and the Sphinx itself, Aigner and Lehner inventoried the different fossils making up the limestone. The fossil fingerprints showed that the blocks used to build the wall of the temple must have come from the ditch surrounding the Sphinx. Apparently, workmen, probably using ropes and wooden sledges, hauled away the quarried blocks to construct the temple as the Sphinx was being carved out of the stone.

That Khafre arranged for construction of his pyramid, the temples and the Sphinx seems increasingly likely. “Most scholars believe, as I do,” Hawass wrote in his 2006 book, Mountain of the Pharaohs, “that the Sphinx represents Khafre and forms an integral part of his pyramid complex.”

But who carried out the backbreaking work of creating the Sphinx? In 1990, an American tourist was riding in the desert half a mile south of the Sphinx when she was thrown from her horse after it stumbled on a low mud-brick wall. Hawass investigated and discovered an Old Kingdom cemetery. Some 600 people were buried there, with tombs belonging to overseers—identified by inscriptions recording their names and titles—surrounded by the humbler tombs of ordinary laborers.

Near the cemetery, nine years later, Lehner discovered his Lost City. He and Hawass had been aware since the mid-1980s that there were buildings at that site. But it wasn’t until they excavated and mapped the area that they realized it was a settlement bigger than ten football fields and dating to Khafre’s reign. At its heart were four clusters of eight long mud-brick barracks. Each structure had the elements of an ordinary house—a pillared porch, sleeping platforms and a kitchen—that was enlarged to accommodate around 50 people sleeping side by side. The barracks, Lehner says, could have accommodated between 1,600 to 2,000 workers—or more, if the sleeping quarters were on two levels. The workers’ diet indicates they weren’t slaves. Lehner’s team found remains of mostly male cattle under 2 years old—in other words, prime beef. Lehner thinks ordinary Egyptians may have rotated in and out of the work crew under some sort of national service or feudal obligation to their superiors.

This past fall, at the behest of “Nova” documentary makers, Lehner and Rick Brown, a professor of sculpture at the Massachusetts College of Art, attempted to learn more about construction of the Sphinx by sculpting a scaled-down version of its missing nose from a limestone block, using replicas of ancient tools found on the Giza plateau and depicted in tomb paintings. Forty-five centuries ago, the Egyptians lacked iron or bronze tools. They mainly used stone hammers, along with copper chisels for detailed finished work.

Bashing away in the yard of Brown’s studio near Boston, Brown, assisted by art students, found that the copper chisels became blunt after only a few blows before they had to be resharpened in a forge that Brown constructed out of a charcoal furnace. Lehner and Brown estimate one laborer might carve a cubic foot of stone in a week. At that rate, they say, it would take 100 people three years to complete the Sphinx.

Exactly what Khafre wanted the Sphinx to do for him or his kingdom is a matter of debate, but Lehner has theories about that, too, based partly on his work at the Sphinx Temple. Remnants of the temple walls are visible today in front of the Sphinx. They surround a courtyard enclosed by 24 pillars. The temple plan is laid out on an east-west axis, clearly marked by a pair of small niches or sanctuaries, each about the size of a closet. The Swiss archaeologist Herbert Ricke, who studied the temple in the late 1960s, concluded the axis symbolized the movements of the sun; an east-west line points to where the sun rises and sets twice a year at the equinoxes, halfway between midsummer and midwinter. Ricke further argued that each pillar represented an hour in the sun’s daily circuit.

Lehner spotted something perhaps even more remarkable. If you stand in the eastern niche during sunset at the March or September equinoxes, you see a dramatic astronomical event: the sun appears to sink into the shoulder of the Sphinx and, beyond that, into the south side of the Pyramid of Khafre on the horizon. “At the very same moment,” Lehner says, “the shadow of the Sphinx and the shadow of the pyramid, both symbols of the king, become merged silhouettes. The Sphinx itself, it seems, symbolized the pharaoh presenting offerings to the sun god in the court of the temple.” Hawass concurs, saying the Sphinx represents Khafre as Horus, the Egyptians’ revered royal falcon god, “who is giving offerings with his two paws to his father, Khufu, incarnated as the sun god, Ra, who rises and sets in that temple.”

Equally intriguing, Lehner discovered that when one stands near the Sphinx during the summer solstice, the sun appears to set midway between the silhouettes of the pyramids of Khafre and Khufu. The scene resembles the hieroglyph akhet, which can be translated as “horizon” but also symbolized the cycle of life and rebirth. “Even if coincidental, it is hard to imagine the Egyptians not seeing this ideogram,” Lehner wrote in the Archive of Oriental Research. “If somehow intentional, it ranks as an example of architectural illusionism on a grand, maybe the grandest, scale.”

If Lehner and Hawass are right, Khafre’s architects arranged for solar events to link the pyramid, Sphinx and temple. Collectively, Lehner describes the complex as a cosmic engine, intended to harness the power of the sun and other gods to resurrect the soul of the pharaoh. This transformation not only guaranteed eternal life for the dead ruler but also sustained the universal natural order, including the passing of the seasons, the annual flooding of the Nile and the daily lives of the people. In this sacred cycle of death and revival, the Sphinx may have stood for many things: as an image of Khafre the dead king, as the sun god incarnated in the living ruler and as guardian of the underworld and the Giza tombs.

But it seems Khafre’s vision was never fully realized. There are signs the Sphinx was unfinished. In 1978, in a corner of the statue’s quarry, Hawass and Lehner found three stone blocks, abandoned as laborers were dragging them to build the Sphinx Temple. The north edge of the ditch surrounding the Sphinx contains segments of bedrock that are only partially quarried. Here the archaeologists also found the remnants of a workman’s lunch and tool kit—fragments of a beer or water jar and stone hammers. Apparently, the workers walked off the job.

The enormous temple-and-Sphinx complex might have been the pharaoh’s resurrection machine, but, Lehner is fond of saying, “nobody turned the key and switched it on.” By the time the Old Kingdom finally broke apart around 2,130 B.C., the desert sands had begun to reclaim the Sphinx. It would sit ignored for the next seven centuries, when it spoke to a young royal.

According to the legend engraved on a pink granite slab between the Sphinx’s paws, the Egyptian prince Thutmose went hunting in the desert, grew tired and lay down in the shade of the Sphinx. In a dream, the statue, calling itself Horemakhet—or Horus-in-the-Horizon, the earliest known Egyptian name for the statue—addressed him. It complained about its ruined body and the encroaching sand. Horemakhet then offered Thutmose the throne in exchange for help.

Whether or not the prince actually had this dream is unknown. But when he became Pharaoh Thutmose IV, he helped introduce a Sphinx-worshiping cult to the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.). Across Egypt, sphinxes appeared everywhere in sculptures, reliefs and paintings, often depicted as a potent symbol of royalty and the sacred power of the sun.

Based on Lehner’s analysis of the many layers of stone slabs placed like tilework over the Sphinx’s crumbling surface, he believes the oldest slabs may date back as far as 3,400 years to Thutmose’s time. In keeping with the legend of Horemakhet, Thutmose may well have led the first attempt to restore the Sphinx.

When Lehner is in the United States, typically about six months per year, he works out of an office in Boston, the headquarters of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, a nonprofit organization Lehner directs that excavates the Lost City and trains young Egyptologists. At a meeting with him at his office this past fall, he unrolled one of his countless maps of the Sphinx on a table. Pointing to a section where an old tunnel had cut into the statue, he said the elements had taken a toll on the Sphinx in the first few centuries after it was built. The porous rock soaks up moisture, degrading the limestone. For Lehner, this posed yet another riddle—what was the source of so much moisture in Giza’s seemingly bone-dry desert?

The Sahara has not always been a wilderness of sand dunes. German climatologists Rudolph Kuper and Stefan Kröpelin, analyzing the radiocarbon dates of archaeological sites, recently concluded that the region’s prevailing climate pattern changed around 8,500 B.C., with the monsoon rains that covered the tropics moving north. The desert sands sprouted rolling grasslands punctuated by verdant valleys, prompting people to begin settling the region in 7,000 B.C. Kuper and Kröpelin say this green Sahara came to an end between 3,500 B.C. and 1,500 B.C., when the monsoon belt returned to the tropics and the desert reemerged. That date range is 500 years later than prevailing theories had suggested.

Further studies led by Kröpelin revealed that the return to a desert climate was a gradual process spanning centuries. This transitional period was characterized by cycles of ever-decreasing rains and extended dry spells. Support for this theory can be found in recent research conducted by Judith Bunbury, a geologist at the University of Cambridge. After studying sediment samples in the Nile Valley, she concluded that climate change in the Giza region began early in the Old Kingdom, with desert sands arriving in force late in the era.

The work helps explain some of Lehner’s findings. His investigations at the Lost City revealed that the site had eroded dramatically—with some structures reduced to ankle level over a period of three to four centuries after their construction. “So I had this realization,” he says, “Oh my God, this buzz saw that cut our site down is probably what also eroded the Sphinx.” In his view of the patterns of erosion on the Sphinx, intermittent wet periods dissolved salt deposits in the limestone, which recrystallized on the surface, causing softer stone to crumble while harder layers formed large flakes that would be blown away by desert winds. The Sphinx, Lehner says, was subjected to constant “scouring” during this transitional era of climate change.

“It’s a theory in progress,” says Lehner. “If I’m right, this episode could represent a kind of ‘tipping point’ between different climate states—from the wetter conditions of Khufu and Khafre’s era to a much drier environment in the last centuries of the Old Kingdom.”

The implication is that the Sphinx and the pyramids, epic feats of engineering and architecture, were built at the end of a special time of more dependable rainfall, when pharaohs could marshal labor forces on an epic scale. But then, over the centuries, the landscape dried out and harvests grew more precarious. The pharaoh’s central authority gradually weakened, allowing provincial officials to assert themselves—culminating in an era of civil war.

Today, the Sphinx is still eroding. Three years ago, Egyptian authorities learned that sewage dumped in a nearby canal was causing a rise in the local water table. Moisture was drawn up into the body of the Sphinx and large flakes of limestone were peeling off the statue.

Hawass arranged for workers to drill test holes in the bedrock around the Sphinx. They found the water table was only 15 feet beneath the statue. Pumps have been installed nearby to divert the groundwater. So far, so good. “Never say to anyone that we saved the Sphinx,” he says. “The Sphinx is the oldest patient in the world. All of us have to dedicate our lives to nursing the Sphinx all the time.”